All complex life forms have some way of recreating aspects of their environments in their brains so that they can take in and respond to the stimuli around them. While the biology is complicated, it essentially boils down to sensory input being transformed into a mental image or perception. There are limits, of course. On average, the human working memory can hold four pieces of information for about 30 seconds before losing it unless extra efforts are made to retain the information. For example, you might remember the sequence 12, 74, 53, 92 for a short time, but unless you find those numbers useful and encode them into long-term memory, you’ll soon forget them.

However, the human brain has found a loophole to the curse of the limits of working memory: chunking, Chunking is the process of breaking information up or even putting information together into chunks that are easy to remember and easy to work with. The advantage is clear: If the human brain can remember four pieces of information for 30 seconds but the pieces are now bigger and more meaningful, the human being can process more information more quickly. For example, if I say that in the year 1264, 53 savages killed 92 bears in a hunt and in 1776, 60 cats were brought to 17 different royal families, you might now be able to remember double the information because it is in chunks of logical data that your brain will respond to. Your brain will be curious why so many bears had to die and interested in the royal families because a natural connection will be made to the year 1776 and, despite the fact that this is false information, suddenly, it is sticking in your memory – the beauty of chunking.

This example wouldn’t work for everyone, though. To children who have no concept of what a year is, except a birthday party and who will not get the reference to 1776, that piece of information will remain irrelevant and will not be processed.

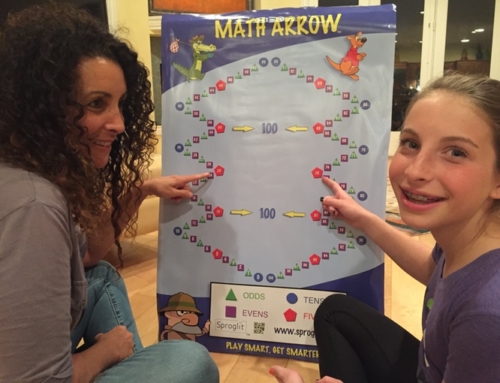

The real value of chunking is amplified by the plasticity of our brains, which allows us to actually change the way we think and encode information through conditioning. This is of course easiest when we are very young because the brains of children are going through a process called intensive learning, the primary acquisition of seemingly unrelated pieces of information. In order to process it, children naturally build up a sort of hierarchical structure of fact combinations and later combinations of those combinations. Math Arrow games such as Kyle Counts use this intensive learning to set up the foundation for chunking information. A child’s brain will subconsciously be looking for patterns when playing the game to get a more complete image of its environment- in this case the screen. Subconsciously, the child will begin memorizing the Math Arrow map in various ways.

First, the animation will keep the child focused. Second, the child will either say aloud, under her breath, or in her head the number to which Kyle is jumping (this is called elaborative rehearsal and is actually a technique for better long-term encoding of information). Third, the child will pay attention to the shapes and colors, chunking groups together by the number being counted. After a while, even looking at the Math Arrow map will provide a memory cue that will cause the child to immediately reflect on existing knowledge. Clearly, the brain of a child is already advanced and ready to absorb new information. Sproglit games are there to make sure the time spent learning new information enters the long-term memory and provides benefits — like a high score on an important math test!